Chapter 1: Introduction

Contents |

The importance of the study of dialect syntax

Introduction

Dialectal variation in the realm of syntax has for a long time been a neglected topic in generative grammar, language typology as well as dialectology. Within the traditions of both generative grammar and language typology the focus has mainly been on standard languages, whereas dialectology has mainly looked at phonological and lexical variation. In the recent past, however, dialect syntax has become a much more prominent topic in linguistics and syntactic properties of dialects are now being studied in a more systematic way. For instance, the ASIS (Syntactic Atlas of Northern Italy) project recorded and analyzed syntactic variation displayed by Northern Italian dialects. The SAND (Syntactic Atlas of Dutch Dialects) project had similar objectives with respect to the dialect variation attested in the Netherlands and Belgium. Large-scale projects of this kind have also started up in other parts of Europe, such as Scandinavia (ScanDiaSyn) and Portugal (DUPLEX, follow-up to CORDIAL-SIN).

A particularly exciting development in the field of dialect research, reflected in these projects, is the increased collaboration of scholars from different linguistic backgrounds: the process of data collection has benefited considerably from insights obtained by dialectology, typology and generative syntax (see for instance the papers in Cornips & Corrigan 2005). In addition, the methodology of data collection has become more sophisticated due to increasing co-operation with sociolinguists (cf. Cornips & Poletto 2005). These developments have thus led to a more interdisciplinary approach to the study of language variation.

In this chapter, we will outline the motivation for studying the syntactic properties of dialects. We will show that this research is necessary to fill an important empirical gap in what we know about dialects (section 2). In addition, there are also strong theoretical reasons for putting the study of dialects high on the syntactic agenda (section 3). In section 4, we will show that empirical and theoretical investigations need not be carried out independently of each other. Indeed, when data collection and the formulation of theoretical questions directly inform each other, we are able to make significant progress in the study of language. We will illustrate our points with examples from the research that was carried out within the SAND project. Section 5 explicates the benefits of carrying out dialect syntax research within a European network. Section 6 gives an overview of the structure of the manual.

Empirical interests

As already mentioned in the introduction, dialect syntax has until recently been a vastly ignored field in linguistics. Although a lot of dialectal variation has been documented, the properties that have been investigated were for a considerable time limited to the domains of the lexicon, phonology and morphology. In fact, it is often denied that dialects exhibit syntactic variation that is worth mentioning. It is the merit of large-scale projects such as ASIS and SAND that they have shown us that syntactic variation is real and pervasive. Even better, they have shown that this variation is not completely random and that clear patterns and correlations can be discerned. Therefore, one reason for studying the syntactic properties of dialects is to fill the empirical gaps that still exist.

For those that believe that dialects are rapidly disappearing, especially in this age of globalization and mass media, the urge for this kind of research is even bigger. This view may in fact be correct for language areas in which dialects have been under severe pressure from the standard language, which is often imposed upon dialect speakers through political means. One can think of Breton as a case in point. Although the SAND project has brought to light an abundance of syntactic variation, we cannot safely conclude that the Dutch dialects, which were the object of study, are stable systems. As the informants used were all aged between 55 and 70 years old, we do not know what the dialects spoken by the younger generations look like. Hence, some properties may have been lost in the meantime. It is therefore good to be aware of an obvious but important fact: the sooner one starts to document the existing variation, the more variation can be captured before extinction.

Dialects may show variation in properties that are also part of the standard language that they are related to. An example from the Dutch dialects would be verbal inflection. The dialects are similar to the standard language in having agreement endings on the verb, for instance, but the endings may differ in their morphological shape and/or in the way they are distributed across the paradigm. More interestingly, dialects may show phenomena that are not part of the standard language. Many dialects of Dutch show, in addition to verbal endings, inflectional endings on the complementizer. This double agreement pattern does not exist in Standard Dutch. In general, doubling phenomena seem to be a pervasive property of dialects. The SAND project has brought to light quite a few of them, such as wh-doubling, subject doubling and negative concord. Examples are given below:

Wh-word doubling:

Wel denkst wel ik in de stad ontmoet heb?

who think-2SG who I in the city met have

'Who do you think I met in the city?'

Subject pronoun doubling and subject agreement doubling:

Ze peiz-n da-n ze ziender rijker zij-n.

they think-3PL that-3PL they they richer are-3PL

'They think that they are richer.'

Negative concord:

't en danst-ij niemand nie.

it neg dances-it nobody not

'Nobody is dancing.'

Had we not studied the Dutch dialects from a syntactic perspective, these phenomena would have gone unnoticed. Hence, we would have ended up with an incomplete picture of the Dutch grammar (‘Dutch’ now being used as an umbrella term for all varieties of Dutch).

Once we have a good picture of the syntactic variation attested in a specific language area, we are in a position to address a number of issues that pertain to the description of the variation and that are standardly part of dialectal research: (i) the geographical distribution of linguistic variables (ii) correlations between distinct linguistic variables and (iii) the correlation between linguistic variation and diachronic change. We will discuss and illustrate each in turn.

(i) Like variation in general, syntactic variation can in principle be random, i.e. arbitrarily distributed across the geographical space. Alternatively, it could show clear patterns. The latter outcome is usually the more interesting one, as systematicity readily invites the search for an explanation. Representing the data cartographically is a particularly useful tool for discerning existing patterns. To give an example: in areas of Limburg, a province in the south-eastern part of the Netherlands, proper names are used with definite determiners, something which is not possible in Standard Dutch. A potential explanation for why this property shows up in Limburg but not in western provinces of the Netherlands is that Limburg borders with Germany, where the use of determiners is widely attested. In short, what helps the formulation of hypotheses is to look at the geographic distribution of syntactic variables.

(iii) A third motivation for studying the geographical distribution of morpho-syntactic phenomena is its potential for strengthening our knowledge of language change. It is generally recognized that linguistic variation can serve as a window on diachronic developments, in that differences between two closely related linguistic systems (that is, dialects) often reflect change within a single system. Hence, part of the variation will reflect the coexistence of retentions and innovations of certain linguistic properties over time. Consulting the historical literature on the area under scrutiny may then suggest which dialect reflects an older stage of the grammar and in which dialect the change has occurred. Dialectal variation may in turn serve as a check on diachronic claims made in the literature. However, historical records will not always be available or will not always be detailed enough to contain examples of the phenomenon under scrutiny. Here, then, synchronic variation can actually serve as input for new hypotheses on diachronic change.

Let us again illustrate these issues with examples from the SAND database. As we have already seen, in some dialects of Dutch it is possible to have the subject, usually a pronoun, doubled by another subject leading to clauses of the type in (1a). There are even dialects with subject tripling, of the type in (1c).

| (1) | a. | Ze | werkt | zij | in | Brussel. | |

| sheweak | works |

shestrong |

|

in | Brussels | ||

| b. | Zij | werkt | zij | in | Brussel. | ||

| shestrong |

works |

shestrong |

|

in | Brussels | ||

| c. | Ze | werkt | ze | zij | in | Brussel | |

| sheweak | works |

sheweak |

shestrong |

in |

Brussels |

Geographically, subject doubling and tripling are restricted phenomena and only occur in dialects spoken in the west and middle part of Belgium (cf. De Vogelaer & Devos 2006). A common and fruitful assumption in dialect geography is that the phenomenon with the most extensive distribution reflects the older stage (cf. Chambers & Trudgill 1998). As non-doubling seems to be the default in Dutch dialects, subject doubling must be the innovation. One would subsequently expect that tripling is an even newer phenomenon. This again seems to be confirmed by its geographical distribution. Tripling is indeed a much more restricted phenomenon than doubling. Moreover, all dialects with tripling seem to allow for doubling as well, so that the group of dialects allowing the former is a proper subset of the latter. Interestingly, subject doubling is most common in second person contexts, suggesting that this is where the phenomenon first showed up. This is indeed confirmed by historical data. Van Helten (1887:282) notes that in Middle Dutch subject doubling only occurs in second person contexts. Hence, synchronic variation can provide clues about diachronic development. The interesting task is then to describe and explain the development from non-doubling to doubling to tripling and to see what the effects are on the status of the subject markers involved.

Theoretical interests

As discussed in the previous section, a first reason for studying dialects is to get a picture of the variation that exists. In addition to this, one may want to use these data for more theoretical concerns in the following sense. An important reason for studying language is to uncover its regularities. Not only are we interested in universal properties, that is, properties that are shared by all natural languages, we would also like to see to what extent regularities exist in the variation that they display. As already pointed out in the previous section, several differences between two language systems may actually boil down to one core difference between them. In that case, the theory is urged to specify the property responsible for all these differences. The attested variation is then essentially reduced.

Although the research strategy just sketched is a clear one and has proven to be extremely useful, it has its inherent intricacies, as for instance observed by Kayne (2000). Suppose that the language systems one compares are English and French. As the number of differences between them is large, it is far from easy to establish which differences are directly related, and should be theoretically linked to one another, and which differences should not. As French is much more similar to Italian, a comparison of these systems increases the chance of linking the correct properties together, although the number of differences between Italian and French is still significant.

From a linguist's perspective, the ideal experiment would involve taking one language, say L, and changing one property to create another language, say L'. A comparison of L and L' will then reveal what the consequences of changing that particular property are for the rest of the grammar. Although this may seem far removed from what is realistic, there is a situation rather close to it. After all, two dialects related to the same standard language will have most of their syntactic properties in common with the standard, as well as with each other. Hence, any syntactic difference between them very much resembles the change from L to L'. Hence, Kayne concludes that comparative dialectal research is possibly as close as one can get to the laboratory situation just described. It therefore holds a great promise of revealing the structure behind language variation and its relevance for the theory of variation is therefore significant.

For any linguistic framework that believes in the existence of language universals, it is important to establish what the boundaries of variation are. As dialectal data significantly enhance the empirical base and often reveal phenomena that are not attested in the standard language, it is essential to include them in the search for these boundaries. For instance, on the basis of Standard Dutch one would be inclined to formulate the theory in such a way as to exclude clauses with more than one nominative argument. However, as we have already seen, dialects of Dutch can have subject doubling and even subject tripling. If we had excluded these data from theoretical consideration, we would have formulated a theory which is too restrictive.

The issue raised by doubling and tripling and its implications for the theory are more complicated than this. There are in fact clear merits to assuming that a clause contains a single subject. In fact, many formal frameworks have formulated constraints that restrict the number of arguments that can appear in a clause. For instance, the Theta Criterion of the generative framework forbids the verb to assign the subject theta role to two arguments. This would in fact give the correct characterization of Standard Dutch, where having more than one subject leads to ungrammaticality. As Standard Dutch is a variety that should also be accounted for, a theory that readily allows for more than one subject would not immediately capture this variety. More generally, generating the subject twice seems to be a semantically vacuous operation. This violates a basic tenet in linguistic research, namely compositionality (Frege 1960), which holds that every element contributes directly to semantic interpretation. From this angle, then, subject doubling as in (2), as well as wh-doubling which an be observed in Dutch dialects (cf. 3) are unexpected phenomena.

| (2) | Zij | werkt | ze | zij | in | Brussel. |

| shestrong | works |

sheweak |

shestrong |

in |

Brussels |

| (3) | a. | Wie | denk | je | wie | ik | in | de | stad | ontmoet | heb? | Dialectal Dutch |

| who | think |

you |

who |

I |

in |

the |

city |

met |

have |

|||

| b. | Wie | denk | je | dat | ik | in | de | stad | ontmoet | heb? | Standard Dutch | |

| who | think |

you |

that |

I |

in |

the |

city |

met |

have |

|||

| 'Who do you think I met in the city?' | ||||||||||||

To conclude, assuming the more restrictive theory leaves the dialects unaccounted for, whereas the less restrictive theory needs an account for why doubling in Standard Dutch is ungrammatical. There are then two ways to proceed.

The first one is to assume that the more restrictive theory is the correct one. If this is so, then only one of the three subjects is a real subject. The first instance of zij in (2) would then for instance have to be a topic, whereas the weak pronoun, ze, functions as an agreement marker rather than an argument bearing a semantic role (in which case we create another doubling configuration, namely doubling of agreement morphology). A second solution, which works particularly well for wh-doubling, is to say that doubling involves the spelling out of more than one link in a syntactic dependency relation that has been created through movement. Although there are obviously some loose ends here, it will be clear in what way consideration of the dialect data steers the analysis: maintaining the (restrictive) theory influences the way in which the subject markers are analyzed.

A second way to proceed is to assume that the less restrictive theory is correct and that there is a particular reason why the standard language does not use doubling. A concrete explanation would be to say that in particular language areas normative pressure has eradicated doubling from the standard variety. This is precisely what Weiss (2002) has proposed for doubling of negation markers in German. He observes that taking into account all varieties of German the use of two negation markers to express a single semantic negation (negative concord) is much more pervasive than a system in which two negation markers cancel each other out and produce a positive statement (double negation). Note that double negation follows from the laws of logic. Under the assumption that prescriptivism relies on intuitive logic to a certain extent, normative pressure expels negative concord from the language system. As dialects are not subject to such pressure, they display negative concord. Of course, there are also standard varieties with negative concord, such as French (ne...pas). One would therefore hope that there is evidence for the hypothesis that normative pressure has got a hold on the standard languages in Germany and the Netherlands, whereas such pressure was either absent or not strong enough in the Romance-speaking countries. Note that an explanation for the absence of subject doubling in Standard Dutch in terms of normative pressure is also useful if one assumes the restrictive theory to be correct. In that event, it serves as an explanation for why the standard language does not use pronouns as topics and agreement markers leading to a doubling or tripling effect.

An important theme, touched upon above but not fully confronted yet, is whether there is a meaningful difference not caused by language-external factors between, on the one hand, the variation attested across languages and, on the other hand, variation within a single language system, which creates what we call dialects. In other words, should we make a distinction between macro- and micro-variation? There is some reason to suspect that this may be true. As we have seen, dialects can have properties not shared by the standard language they are related to, such as subject doubling/tripling, but at the same time be very similar to it. It is, for instance, striking that there is no variety of Dutch with a basic word order that is VO. That is, all dialects of Dutch are like Standard Dutch in displaying a basic OV word order. This suggests that the OV order is a defining property of Dutch in all its variants, whereas subject doubling/tripling is not. In order to account for the variation in one domain and at the same time account for the stability in another domain, one may therefore decide that macro- and micro-variation should be encoded differently in the theory. One way of doing that would be to use macro- and micro-parameters and define these notions in such a way that they make predictions as to what variation can exist across standard languages and across dialects. Although it is for the moment unclear how to do that exactly, it could turn out that using two theoretical constructs applying to different kinds of variation is unnecessary. It is possible that macro-variation is caused by core features of the grammar, such as tense and agreement, whereas micro-variation targets features that are more peripheral and have a less drastic effect on the variation (cf. Barbiers 2006). The task is then to find the features that allow us to make the relevant distinction between core and periphery. That is, one should answer which core property the OV/VO property is related to and which peripheral feature causes subject doubling/tripling.

Empirical and theoretical interaction

We have seen that the search for new data can be steered by empirical curiosity and interest in the geographical distribution of morpho-syntactic variables, as well as by purely theoretical concerns. In practice, research will not always start from either empirical or theoretical concerns but from both, as theoretical questions raise empirical ones, and vice versa. New data will shed a new light on the theory and theoretical developments will raise new empirical questions. Hence, they are mutually reinforcing precesses.

In this section, we will give two examples of this interplay, based on two dissertations that were written within the SAND project. Van Craenenbroeck (2004) looks at ellipsis in Dutch dialects. Van Koppen (2005) looks at complementizer agreement focusing on clauses with conjoined subjects. The SAND project consisted of two stages. The initial stage involved general data collection, on the basis of a written questionnaire and of oral interviews. There were two main results coming out of this stage, namely the syntactic atlas of the Dutch dialects (Barbiers et al. 2005, Barbiers et al. in press), and the online digital database containing all the data collected, as well as a cartographic tool. On the basis of this general data collection, specific topics were chosen for more in-depth studies at the second stage. This necessitated the compilation of additional questionnaires, which were sent to a restricted number of locations. The dissertations by Van Craenenbroeck and Van Koppen are the output of this second process. Let us look at each in turn.

Ellipsis in Dutch dialects (Van Craenenbroeck 2004)

Van Craenenbroeck's research on ellipsis is couched within an ongoing debate in the generative literature about the correct analysis of ellipsis. The central issue is how to characterize the nature of the elided site. Take an example like (4):

(4) a. Mary doesn't love Peter.

b. Yes, she does.

The b-reply contains ellided structure, basically the VP love Peter from (4a). There are two pervasive proposals on offer, one view is that the ellided site is an empty proform with no internal structure, as in (5).

(5) Yes, she does pro.

The competing view has it that the elided site has internal structure but that the constituents in it are unpronounced, indicated in (6) by strikethrough.

(6) Yes, she does [VP love Peter].

As Van Craenenbroeck shows, Dutch dialects have particular constructions that shed new light on this debate. What he ends up concluding is that both the ‘proform’ view and the ‘unpronounced structure’ view are correct, albeit for different constructions. He discusses two: one he coins the Sluicing Plus Demonstrative (SPD) construction, the other the Short Do Reply (SDR) construction. Let us look at each in turn.

A typical example of a SPD construction is given in (7), from the Wambeek dialect. One can observe that the clause with ellipsis contains a WH-element followed by a demonstrative pronoun.

| (7) | Jef | eid | iemand | gezien, | mo | ik | weet | nie | wou | da. | (Wambeek) |

| Jef | has |

someone |

seen |

but |

I |

know |

not |

who |

that |

Da is a distal demonstrative pronoun, so that one could be tempted into a ‘proform’ analysis. Van Craenenbroeck, however, argues that the SPD construction stems from an underlying cleft construction of the type in (8). Hence, the analysis he proposes is the one in (9):

| (8) | Wou | is | da | da | Jef | gezien | etj. |

| who | is |

thatDEM |

thatCOMP |

Jef |

seen |

has |

| (9) | Ik weet nie [CP1 wou [CP2 da [IP tda |

Several pieces of evidence showing the similarity of SPD constructions and clefts can be put forward. First, they display similar case patterns. If, as an answer to (10a), a WH-word is used, it must appear in the same case form as the argument in (10a), namely nominative. This is also true for an SPD-answer to (10a). If, however, the argument in the first sentence is in the accusative, the WH-word answer is also in the accusative (cf. 11b), whereas the SPD-answer uses a nominative form (cf. 11c).

| (10) | a. | 't | Kumt | murrege | inne | noa | 't | feest. | (Waubach) |

| there |

comes |

tomorrow |

someone |

to |

the |

party |

|||

| b. | Wea/ | *Wem? | |||||||

| whoNOM | whoACC |

||||||||

| c. | Wea/ | *Wem | dat? | ||||||

| whoNOM | whoACC | thatDEM |

|

(11) |

a. | Ich | han | inne | gezieë. |

| I | have |

someone |

seen | ||

| b. | *Wea/ | Wem? | |||

| whoNOM | whoACC | ||||

| c. | Wea/ | *Wem | dat? | ||

| whoNOM | whoACC | thatDEM |

| (12) | Wea | is | dat | deste | gezieë | has? |

| whoNOM | is |

that |

that-you |

seen |

has |

| (13) | Lewie | ei | me | bekan | iederiejn | geklapt. |

| Lewie | has |

with |

almost |

everone |

spoken | |

| a. | Me | wou | nie/ | wel? | ||

| with | who |

not |

AFF |

|||

| b. | *Me | wou | da | ? | ||

| with | who |

not/AFF |

thatDEM |

not/AFF |

| (14) | *Me | wou | was | da | da | Lewie | geklapt | ou? | ||

| with | who | not/AFF |

was |

that |

not/AFF |

that |

Lewie |

talked |

has |

The Short Do Reply construction that appears in some Dutch dialects resembles the familiar English one Yes, X does.

| (15) | a. | Marie | zie | Pierre | nie | geirn. |

| Marie | sees |

Pierre |

not |

gladly | ||

| b. | Jou | ze | duut. | |||

| Yes | she |

does |

| (16) | a. | There were not many people at the party. |

| b. | Yes, there were. |

| (17) | I know which chisel Ed likes and which one he doesn't. |

Now, the phrase which one must have moved to clause-initial position from its base position. If the ellided site is a structure-less proform, this base position is not available. If, on the other hand, the elided site is structured but unpronounced, this base position is included and the grammaticality of (17) unproblematic. The interesting observation is now that corresponding examples in the Dutch dialects are ungrammatical:

| (18) | a. | Dui | stonj | drou | mann | inn | of. |

| there | stood |

three |

men |

in-the |

garden | ||

| b. | *Dui | en | doenj. | ||||

| there | NEG |

doplural |

| (19) | a. | Ik | weet | wou | da | Marie | geire | zie. |

| I | know |

who |

that |

Marie |

gladly |

sees | ||

| b. | *En | wou | en | duu-se? | ||||

| and | who |

NEG |

does.she |

|||||

| 'And who doesn't she?' | ||||||||

If the data in (16) and (17) are indicative of structure being present but unpronounced, we must conclude that the elliptic constructions in (18b) and (19b) contain a proform.

The contribution that Van Craenenbroeck makes is threefold. First, there are dialect/construction-specific contributions. By analyzing SPD-constructions as deriving from clefts, we capture their similar properties. By analyzing SDR-constructions as involving a proform, we understand the ungrammaticality of (18b)-(19b). Second, there is a contribution to generative theory: both a ‘proform’ and a ‘unpronounced structure’ approach to ellipsis are needed. Third, there are methodology-specific contributions: the importance of dialects is underscored. There is a clear interplay between the study of dialects and the theory of grammar. Constructions from dialects are used to bear on a theoretical debate. Conversely, without the generative background and the discussion about proforms and unpronounced structure, examples like (18a) and (19b) would in all likelihood not have been tested out on dialect speakers. Hence, the differences with English would have gone unnoticed.

Agreement in coordination (Van Koppen 2005)

Van Koppen (2005) looks in detail at complementizer agreement in Dutch dialect and focuses on constructions in which the complementizer is followed by a conjoined subject. Two patterns can be observed. In some dialects, the complementizer shows first conjunct agreement (FCA). An example is (20a), in which des agrees with doow, the first conjoined subject. Alternatively, there are dialects in which the complementizer agrees with the conjoined subject as a whole. In (20b), it appears in the plural.

| (20) |

a. |

Ich | dink | de-s | doow | en | ich | ôs | kenne | treffe. |

(Tegelen) |

| I | think | that2.SG | [you2.SG | and | I]1.SG |

each.other | can | meet | |||

| b. | Kpeinzen | da-n | Valère | en | Pol | morgen | goa-n | (Lapscheure) | |||

| I.think | thatPL | [Valère | and | Pol]3.PL | tomorrow | go |

These constructions raise at least the following questions. First, we would like to know what the nature is of these dependencies: how are they encoded and where in the grammar? Second, what determines the spell-out form of the complementizer?

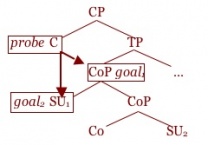

Van Koppen’s approach is informed by developments in the minimalist programme that take agreement relations to be asymmetric. A so-called probe is the element needing to agree (here, the complementizer) and the element determining the agreement (here, a subject) is called a goal. In any clause with more than one subject, the complementizer has in principle more than one goal it could agree with, but it usually agrees with the most local subject. Now, Van Koppen argues for a specific definition of locality, which states that α and β are equally close to a probe if they share the same set of c-command nodes. Take a look at (21).

| (21) |

As there is no node c-commanding goal1 but not goal2, the syntax cannot decide which goal the complementizer is supposed to agree with. As a consequence, this structure is passed on to the phonology without any instruction added by the syntax. The phonological component consults the paradigm of complementizer agreement, looks at the affixes associated with goal1 and goal2 and then spells out the affix that is most specific.

Let us see how this works. In (22) the paradigms are given for the Tegelen and Lapscheure dialect, respectively.

| (22) | SG | PL | SG | PL | |||

| 1st | - | - | 1st | -n | -n | ||

| 2nd | -s | - | 2nd | - | - | ||

| 3rd | - | - | 3rd | - | -n |

Tegelen basically has one agreeing form, 2nd person sg des, and a default form det in the other contexts. Suppose that the syntactic structure has a 2nd person sg pronoun as the first conjunct. In that case, spelling out this agreement relation wins out over spelling out agreement with the conjoined subject as a whole, as des is more specific than det. This is what we find, as can be observed in (20a). Lapscheure has an overt affix -n in 1st person contexts and one in 3rd person pl. contexts. No agreement is spelled out in the other contexts. This means that in the same syntactic structure, the agreement relation with the conjoined subject as a whole is spelled out, because -n is more specific than no agreement. This is what we find in (20b).

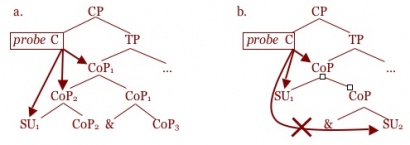

Several predictions follow from this analysis. First of all, nothing should in principle prohibit the complementizer from agreeing with a subject that occupies the specifier position in the first conjunct. As can be seen in (24a), this constituent shares the same set of c-commanding nodes with the conjoined subject forming the first conjunct (CoP2), as well as with the conjoined subject as a whole (CoP1). The second prediction is that agreement with the second conjunct should be out. In the structure in (24b), the head of CoP, &, c-commands SU2 but not SU1 or CoP. Hence, SU2 is not equally local to C.

| (24) |

Both predictions are correct, as can be observed in (25a) and (25b), respectively.

| (25) | a. | de-s | doow | en | Marie | en | Jan | en | Piet | morgen | komme. | (Tegelen) |

| that2.SG | [you2.SG |

and |

Marie] |

and |

[Jan |

and | Piet] | tomorrow |

come |

|||

| b. | *de-s | Marie | en | doow | uch | treffe. | (Tegelen) | |||||

| that2.SG | [Marie |

and |

you2.SG |

each.other | meet |

A more general prediction is the following. As in Van Koppen's proposal the nature of the dependencies is syntactic and not phonological, as could in principle be the case, there should not be an adjacency requirement on the complementizer and the (conjoined) subject. This is correct, as can be observed in (26), where adjacency is disrupted by adverbial material:

| (26) | a. | da-n | zelfs | Valère | en | Pol | morgen | goan. | (Lapscheure) | |

| that3.PL | even |

Valère |

and |

Pol |

tomorrow |

go |

||||

| b. | de-s | auch | doow | en | Marie | zulle | moete | danse. | (Tegelen) | |

| that2.SG |

also |

you2.SG |

and |

Marie |

will |

have.to |

dance |

An additional issue that Van Koppen takes up is that of movement of subjects. A general assumption within the generative framework is that if a syntactic constituent moves to another position in the clause, the position it moves from is marked. The standard view nowadays is that the original position of the moved constituent contains a copy of this constituent. Van Koppen, however, observes that in constructions in which the complementizer agrees with the first conjunct, agreement disappears if the conjoined subject moves across the complementizer to the main clause.

| (27) | Doow | en | Marie | denk | ik | ?det/ | *de-s | het | spel | zulle | winnen. |

| [you2.SG | and |

Marie] |

think |

I |

that |

that2.SG |

the |

game |

will |

win |

If his subject leaves a compy, the question is why first conjunct agreement would be ungrammatical, since the syntactic dependency can be established in the mapping of syntax to phonology. Van Koppen therefore proposes that the internal structure of copies is inaccessible for agreement relations. Only the top node of the conjoined subject, which is by definition plural, can be 'seen' by the syntax. This hypothesis makes a few predictions. First of all, agreement with a coordinated subject should not be lost after movement across the complementizer, as the top node is accessible for agreement relations. This prediction is correct, as (28) shows.

| (28) | ?Pol | en | Valère | peinzen-k | da-n | morgen | goan | komen. | (Lapscheure) |

| [Pol | and |

Valère] |

think-I |

that3.PL |

tomorrow |

go |

come |

Second, agreement with a non-coordinated subject should not be lost, as the internal structure of the copy is again irrelevant for establishing the agreement relation.

| (29) | Doow | denk | ik | de-s | de | wedstrijd | zal-s | winnen. | (Tegelen) |

| you2.SG | think |

I |

that2.SG |

the |

game |

will |

win |

The research results obtained again make contributions on several levels. The dialect/construction-specific contribution is the conclusion that syntactic restrictions on agreement dependencies show no variation. Dialectal variation in agreement forms spelled out on the complementizer can be predicted from the paradigm for complementizer agreement that the dialect happens to have. Second, the contribution to generative theory is the specific definition of locality it argues for, as well as the way in which two distinct modules of the grammar, syntax and phonology, are involved in the surface output of dependency relations. In addition, it contributes to our understanding of syntactic dependencies and specifically the properties of copies. Third, there are methodology-specific contributions. Again, the study of dialects can provide new arguments and insights in a theoretical debate. Moreover, without the generative discussion about locality some of the predictions would not have been tested. This would have led to an incomplete picture in the phenomenon.

Towards dialect syntax on a European scale: the Edisyn project

After a period in which dialectal research largely focused on lexical and (morpho-)phonological variation, the study of syntactic variation across dialects has seriously taken off and, especially in the last decade, data are being gathered in a much more systematic way. Since large-scale projects are either running or being set up, we believe it makes sense to see whether some standardization can be achieved that allows us to reach long-term goals more easily. It is to this end that the Edisyn (European Dialect Syntax) project has been developed. In this section we will give more information about this project and we will present some initial results.

The goal of the Edisyn project is twofold. One is to establish a European network of (dialect) syntacticians that use similar standards with respect to methodology of data collection, data storage and annotation, data retrieval and cartography. Secondly, we believe that a network will be more coherent, and collaboration enhanced, if we make sure that there is some empirical overlap in what is being studied throughout Europe. A second goal is therefore to compile an extensive list of doubling phenomena from European languages and dialects and to study them as a coherent object. Cross-linguistic comparison of doubling phenomena will enable us to test or formulate new hypotheses about natural language and language variation. (We will return to the topic of syntactic doubling in the end of this section.) A comparative angle can be most fruitfully employed if the data that are used are comparable to a reasonable extent. To this end, some methodological and empirical standardization is desirable.

How do we set up a successful network? We think that such a network should involve as many linguists as possible and that, for this reason, theoretical commitments should help rather than hinder the setting up of large-scale dialect syntax projects. The initial stages will mostly involve data collection. Although theoretical linguistics can be helpful in suggesting which phenomena should be investigated, the search should not be constricted by a too myopic view from one's favourite theoretical framework. In order to limit the chances of missing substantial variation in the data gathering process, a project should ideally be formed by linguists coming from different linguistic backgrounds. A reason to believe that this is true is the success of the SAND-project, which involved a collaboration between dialectologists, generative linguists, typologists and socio-linguists. Of course, once the data have been collected, researchers are free to approach them with the theoretical tools of their choice.

Besides getting as many linguists interested as possible, the creation of a network will be facilitated by formulating concrete short-, intermediate and long-term goals. Short-term goals include making inventories of resources: departments, institutes and individual researchers working on dialect syntax, inventories of bibliographies of publications, inventories of existing databases and, last but not least, an inventory of funding possibilities. The Edisyn project has taken the initiative in this and most of this information is made public on this website.

An intermediate goal is to create a European perspective on dialect syntax. After the inventorization stage and before the actual data collection some thought has to be put into the minimal methodological and technical requirements, i.e. some level of standardization. Of course, this stage can benefit from large-scale projects that have been successfully completed, such as the SAND and ASIS, but it is not certain beforehand that these experiences will be useful in every situation in Europe. It is therefore important that there will be an ongoing discussion among members of the network that will eventually create a common ground that is workable for all researchers involved and will at the same time not stand in the way of all the flexibility needed to approach geographical/social spaces with their own individual characteristics. This for instance involves defining a set of phenomena that are relevant for all languages included, or at least a substantial subpart (Slavic, Romance, Germanic), such as clitics, negation, complementizers, wh-constructions, expletive constructions and syntactic doubling. Similar discussions will have to lead to a consensus on the required level of theory specificity and, relevant at later stages, the labels used in the tag set.

An obvious long-term goal is for researchers to store and annotate the data that they collect in a systematic way, and to submit them to dialectological, typological, formal and quantitative analysis. A good way of making the results available to a more general audience is to make a syntactic atlas, which is a series of maps based on a selection of the collected data. Particularly interesting, and this is where the European perspective will pay off, is to try to combine the research results. A straightforward way of doing this is to combine electronic databases and make it possible to search them from one location, preferably through a web-browser that can tap into several, as well as different types of, databases. The Edisyn project has taken the first steps in establishing what the technical requirements are to make this possible, which are by no means excessive once some minimal standardization principles have been observed during the data collection and storage.

With a network in place, a bird's eye view on dialects across Europe and the combining of databases are likely to reveal cross-dialectal patterns and raise new research questions. Subsequently, it should be relatively easy for research groups within the network to engage in collaborative research. To give one example: the SAND-project has indicated that a subset of the Dutch dialects, mostly those in the southern part of the Netherlands as well as dialects in Belgium, allow participle doubling of the type in (30). In addition to the lexical participle, the clause contains a participial form of the auxiliary hebben 'to have', which in turn is selected by a finite form of hebben:

| (30) | Ik | heb | vandaag | nog | niet | gerookt | gehad. | Dialectal Dutch/*Standard Dutch |

| I | have |

today |

still |

not |

smoked |

had |

It turns out that participle doubling can also be found in dialects of Italian (Cecilia Poletto, p.c.) as dialects of Occitan (Patrick Sauzet, p.c.). It will therefore be interesting to see if a cross-dialectal comparison of these constructions can bring out the similarities and differences in their syntactic, as well as semantic, properties.

The cross-dialectal existence of participle doubling, which is no doubt more pervasive than we now think, was brought to our attention during an exploratory workshop on syntactic doubling constructions in dialects of Europe, held at the Meertens Institute in March 2006. The same workshop confirmed our suspicion that doubling is a pervasive phenomenon in dialects. Papers were presented by members of the existing network coming from different linguistic backgrounds. They all presented examples of doubling. The overall picture that emerges is that syntactic doubling in dialects of Europe is attested in at least the following empirical domains:

- the pronominal domain (e.g. subject doubling, clitic doubling/duplication, wh-word doubling, relative pronoun doubling, possessor doubling, locative pronoun doubling, resumption)

- the extended verbal domain (e.g. agreement doubling, tense/aspect/modality doubling, infinitival marker doubling, participial morphology doubling (the Participium Pro Infinitivo effect), infinitival morphology doubling (the Infinitivum Pro Participio effect), doubling of auxiliaries (be, have, go, let), periphrastic (non-emphatic) do-support, double complementizers, complementizer agreement, lexical verb doubling)

- the extended nominal domain (e.g. preposition doubling, comparative and superlative doubling, double definiteness, demonstrative reinforcement)

- the quantifier system (e.g. focus particle doubling, negative concord, floating quantifier doubling, (in)definite determiner doubling).

In this section we have explained why it is beneficial to establish a network for the study of dialect syntax and have formulated short-, intermediate- and long-term goals that would make the creation of the network more concrete. In addition, we have seen an initial result: doubling is a very pervasive phenomenon in dialects of Europe. It is to be expected that other generalizations and other properties of dialects will emerge once European collaboration takes off on a larger scale.

References [incomplete]

Barbiers, Sjef (2005). ‘Word order variation in three-verb clusters and the division of labour between generative linguistics and sociolinguistics’, in Leonie Cornips & Karen Corrigan (eds.), Syntax and variation. Reconciling the biological and the social, John Benjamins, Amsterdam 233-264.Barbiers, Sjef, Hans Bennis, Gunther de Vogelaer, Magda Devos & Margreet van der Ham (2005). Syntactic atlas of the Dutch dialects. Volume 1. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam.

Barbiers, Sjef (2006). ‘Er zijn grenzen aan wat je kunt zeggen’ [There are limits to what you can say], Inaugural lecture, University of Utrecht, 1 June 2006.

Barbiers, Sjef, Hans Bennis, Gunther de Vogelaer, Magda Devos & Margreet van der Ham (in press). Syntactic atlas of the Dutch Dialects. volume 2. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam.

Barbiers, Sjef, Margreet van der Ham, Olaf Koeneman & Marika Lekakou (eds.) forthcoming. Syntactic doubling in the dialects of Europe. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Belletti, Adriana (2003). ‘Extended doubling and the VP periphery’, ms., University of Siena.

Bennis, H. (2001). 'Alweer wat voor (een)'. In B. Dongelmans, J. Lalleman & O. Praamstra (eds.), Kerven in een rots. Leiden: SNL. 29-37.

Chomsky, Noam (1995). The minimalist program. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Craenenbroeck, Jeroen van (2004). Ellipsis in Dutch dialects. PhD dissertation, University of Leiden.

De Vogelaer, Gunther (2005). Subjectsmarkering in de Nederlandse en Friese dialecten. PhD. dissertation, University of Gent.

Grohmann, Kleanthes (2003). Prolific domains: On the anti-locality of movement dependencies. John Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia.

Haegeman, Liliane (1995). The syntax of negation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Koppen, Marjo van (2005). One probe - two goals: Aspects of agreement in Dutch dialects. PhD dissertation, University of Leiden.

Nunes, Jairo (2004). Sideward movement and the linearization of chains. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Nuyts, Jan (1995). ‘Subjectspronomina en dubbele pronominale constructies in het Antwerps’. In Taal & Tongval 47: 43-58.

Rizzi, Luigi (1996). ‘Residual V2 and the Wh-Criterion’, in Adriana Belletti & Luigi Rizzi (eds.), Parameters and functional heads. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 63-90.

Torrego, Esther (1998). The dependencies of objects. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Uriagereka, Juan (1995). ‘Aspects of the syntax of clitic placement in Western Romance’, Linguistic Inquiry 26: 79-123.

Vandekerckhove, Reinhild (1993). ‘De subjectsvorm van het pronomen van de 2e p. ev. in de Westvlaamse dialecten’. In Taal & Tongval 45: 173-183.

Weiss, Helmut (2002). ‘Three types of negation: A case study in Bavarian’, in Sjef Barbiers, Leonie Cornips & Suzanne van der Kleij (eds), Syntactic microvariation. Electronic Publication, Meertens Instituut: www.meertens.knaw.nl/books/synmic

Zeijlstra, Hedde (2004). Sentential negation and negative concord. PhD Dissertation, University of Amsterdam.

Zeijlstra, Hedde (2006). ‘Negative doubling in Dutch’, talk delivered at the Workshop on syntactic doubling in the dialects of Europe, Meertens Instituut, 16-18 March 2006.